Biden, Fetterman, & The 11th Century "Weekend at Bernie's"

The recent performance by John Fetterman in the Pennsylvania Senate debate has sparked a sharp discussion about the wisdom of his candidacy. The evidence of Mr. Fetterman’s cognitive impairment, due to his unfortunate stroke, was so clear that some critics have wondered if Mr. Fetterman is actually making his own decisions or if they are being made by his team. In turn, this has inevitably spilled over into a discussion or, more accurately, an intensification of the discussion of President Biden’s own mental condition.

One consequence of that renewed discussion is the reappearance of memes that recall the 1989 black comedy, Weekend at Bernie’s, in which Bernie, an insurance executive who has perpetrated a fraud, is murdered just as two low-level employees arrive at his house for the weekend. In order to protect their own safety, the two employees create the illusion that their former boss is still alive by using Bernie’s corpse as a prop at parties, dinners, and even a waterskiing event. Even more erudite sites, such as the conservative website Power Line, have been unable to resist and posted its own “Weekend at Biden’s” parody.

In both cases, conservative critics have questioned whether Biden and Fetterman are mere exanimate figureheads being manipulated by their advisors and used to galvanize voters who may be less enthusiastic about another candidate.

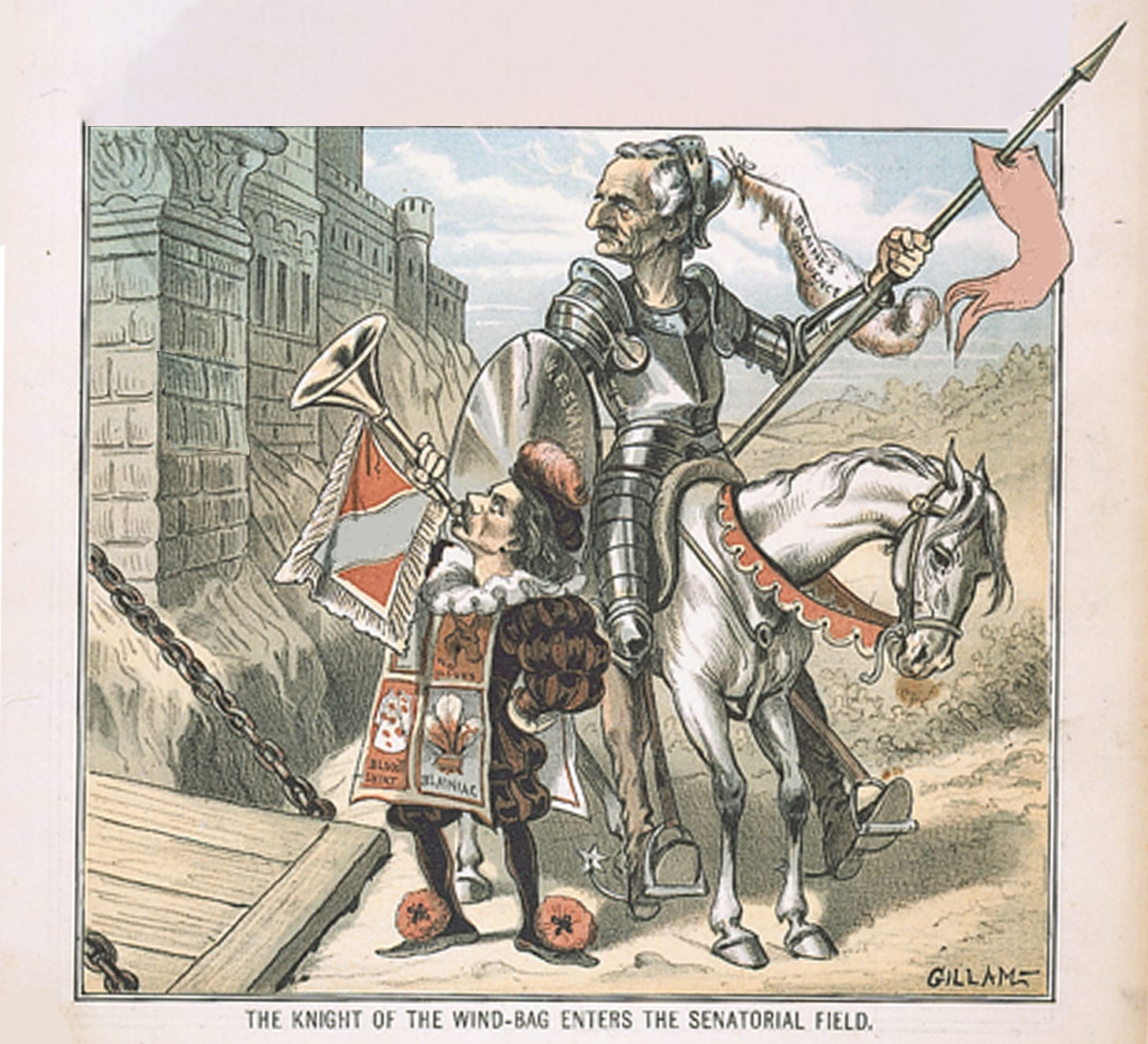

Whether true or not, the idea of using an empty suit as a prop for some ulterior purpose is not original to the modern political landscape or cult ‘80s films. In fact, history provides a famous example, one rescued from obscurity by poets, playwrights, composers, and filmmakers -- Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, an 11th Century Castilian knight known otherwise as El Cid. According to legend, El Cid was a famous Spanish general who died on the eve of a great and determinative battle against the Berbers. Rather than risk demoralizing the Spanish troops by revealing his death, El Cid’s wife supposedly instigated a plan to place his body, concealed within his knight’s armor, on his horse, whereupon it led the Spanish army to a glorious victory and relieved the siege of Valencia.

El Cid was immortalized by the oldest surviving Castilian epic poem, El Cantar de mio Cid. He was subsequently the subject of a play by the French tragedian, Pierre Corneille, an opera by Jules Massenet, and a 1961 film starring Charlton Heston as El Cid and Sophia Loren as his wife, Jimena. Unsurprisingly, over the centuries, the person of El Cid became less known for the exploits of his life, and more for his wife’s use of his lifeless body after his death.

However, the story of El Cid is more than a good yarn; it provides a lesson in how the mythologizing of a man’s deeds can render him larger than life to succeeding generations. For the real story of El Cid, while colorful in its own right, is far more prosaic and nuanced than that portrayed by the legend. El Cid was born into a family of minor nobility and was brought up at the royal court of Ferdinand I in the household of his son, Sancho II. After Sancho succeeded his father to the throne, El Cid was appointed as his standard bearer at an early age, whereby he established a strong military reputation. While campaigning with Sancho in a war against Sancho’s younger brother, Alfonso, to reunite their father’s kingdom, El Cid found himself in a precarious position when the childless Sancho died, leaving Alfonso as his heir and El Cid’s new ruler. El Cid survived this turn of events, in part by marrying Alfonso’s niece, the aforementioned Jimena, but he eventually was driven into exile.

El Cid thereafter served as a general for the Muslim King of Zaragoza, defeating, on the king’s behalf, both Moorish and Christian armies. However, he was recalled to the service of Alfonso, after the latter was crushingly defeated by the Almoravid invaders at Sagrajas. El Cid subsequently conquered the city of Valencia in 1094. He ruled that city, only nominally on Alfonso’s behalf, until his death five years later, after he had relieved a later siege by the returning Almoravids. He was succeeded as ruler by Jimena.

A while after his death, El Cid’s body was moved to Burgos. Reportedly, Jimena arranged for his body, dressed in his armor, to ride his horse in the funeral procession when it entered the city, possibly providing the basis for the subsequent legend.

With the passage of time, it is difficult to discern how the marketing consultants of El Cid’s day were able to transform the material of his life into the stuff of legend. How did a man, whose life can be characterized as one purely in the pursuit of self-interest, who rarely fought for his country but rather fought in the internecine wars of the Spanish succession, who led Moorish armies against his own countryman, and who returned to fight for Spain against the Muslim invaders primarily in order to achieve his personal goal of ruling Valencia, become a national hero who has been celebrated for centuries? However the legend was created, one suspects that it proved more useful to El Cid’s successors than it ever did to him.

Both supporters and critics of Joe Biden might see echoes of El Cid in the life of the President. Supporters will see a man who was victoriously at the forefront of all of his country’s political wars of the time. Opponents will see a man who finally came to rule more as a result of his unerring sense of when to switch sides than to any accomplishment of his own. Moreover, observers might see stronger echoes of Jimena in the life of Jill Biden, as well as that of Giselle Fetterman.

Nevertheless, however one views the current President, it is unlikely he will ever become the subject of his own epic poem, unless, perhaps, it celebrates his arrest in South Africa while supporting Nelson Mandela or his showdown with the notorious Corn Pop. More likely, if his legend is to live on, it will be, whether deservedly or undeservedly, like that of El Cid, the lifeless man on the horse. While the President’s most mean-spirited critics will see this as the stuff of comedy, clearer thinkers will see this as the stuff of tragedy, as John Fetterman graphically demonstrated last week.