The Israeli-Hamas conflict has returned to the forefront of the news with the execution by Hamas of six Israeli hostages. Much of the Western world has responded in a way that would appear decidedly counter-intuitive – it has blamed, not Hamas, but Israel for the murder of its citizens. Thus, President Biden, when questioned about the murder, answered that Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu was “not doing enough” to achieve a deal for the remaining Israeli hostages. The United Kingdom announced that the Starmer government was suspending the delivery of certain weapons to Israel. This came weeks after the Biden-Harris administration had similarly announced that it was suspending the shipment of certain arms. Even within Israel, thousands have protested the absence of a hostage agreement between Israel and Hamas.

The pressure on Israeli is nothing new. Since the shock of October 7th has receded in memory, restraints have been placed on virtually every aspect of Israel’s conduct of the war. The Biden administration placed a so-called red line on Israel’s incursion into Rafah, the World Court issued an indictment of Israel for its alleged failure to feed Palestinian refugees, and calls have abounded for Israel’s response to be “proportionate,” although, as some writers put it after Hezbollah’s rocket attack on northern Israel, what is a proportionate response to the killing of twelve children, the killing of an equal number? Now, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is under pressure to soften his position with respect to the remaining hostages.

To anyone familiar with Arab-Israeli relations, the reaction of the world is depressingly familiar. From the time of the Versailles Treaty in 1919 onward, Western attempts to broker a two-state solution have followed a reflexive and unwavering pattern: the West makes a proposal, Israelis make concessions, Arabs refuse to do the same, instead resorting to violence, and Western interlocutors return to seek more concessions from Israelis. As Winston Churchill said more than 100 years ago, “[I]t is not fair to come to a discussion thinking that one side has to give nothing and the other side has to give large and important concessions, and without any security that these concessions will be a means of peace.”

Nevertheless, Netanyahu’s position with respect to the hostages – that any ceasefire must allow for Israel’s continued occupation of Gaza’s border with Israel – drew support from at least one unlikely source: the New York Times. In a piece written earlier this week, columnist Bret Stephens writes that Netanyahu is “right.” He argues that concern for the hostages must be weighed against the larger consequences of accepting conditions that will cause even greater harm to Israel.

Stephens’ reasoning has a long tradition in American military thought. More particularly it echoes that of many major figures of the American Civil War, including Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and, most notably, William T. Sherman.

Sherman and “Hard War”

While history has treated many leaders of the Civil War as legendary figures, one such figure has perhaps not received his entire due by the general public. While Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are renowned for their audacity and tactics, and while Grant is considered by many to be the savior of the Union, the figure regarded by most historians as the preeminent military thinker of the Civil War was William Tecumseh Sherman. As the famed British strategist and historian, B.H. Liddell Hart, wrote in the preface to his biography of Sherman, “William Tecumseh Sherman, by the general recognition of all who met him, was the most original genius of the American Civil War.”

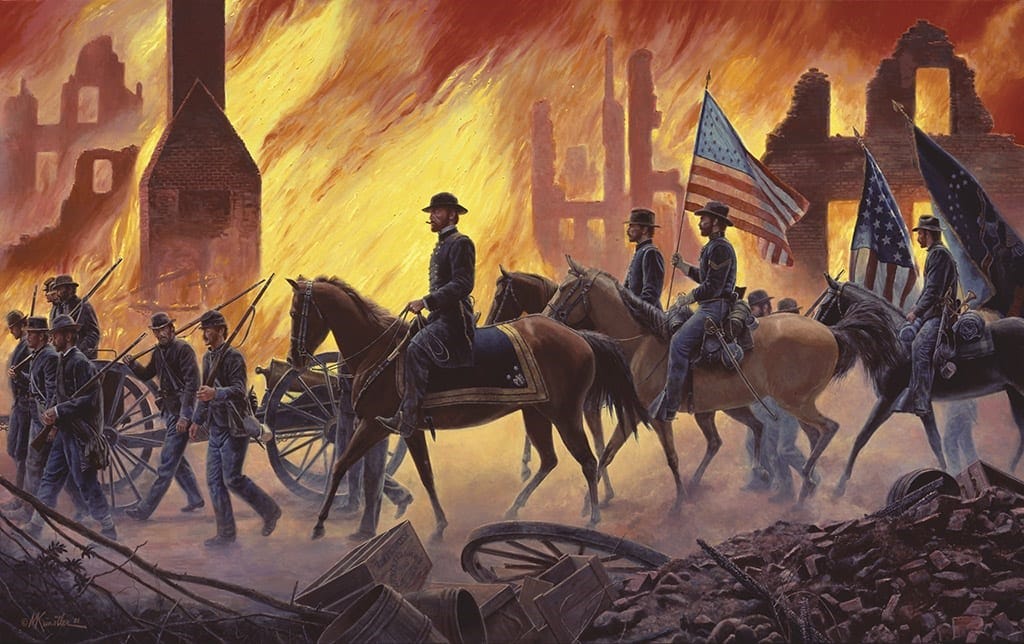

Sherman is most famous for his so-called March to the Sea where, after the capture of Atlanta, he cut loose from his line of supplies, marched across Georgia, living off the land and destroying crops and other property that could be of use to the Confederate armies. Yet, his campaign prior to the capture of Atlanta, was perhaps an even greater achievement. Marching from Tennessee to Atlanta, Sherman effected the capture of that city almost entirely by maneuver. With one exception, he avoided entirely pitched battles, completing one of history’s most successful campaigns with Union casualties that were a fraction of those incurred by Grant during the same period.

Sherman was a proponent of total war against the Confederacy, even though he was sympathetic to the South and was even serving as president of what would become Louisiana State university when war broke out. After his seizure of Atlanta, Sherman persuaded Grant that his strategic objective should be not the destruction of the only remaining Confederate force facing him, as Grant had originally ordered, but the destruction of the South’s will to fight, and its material capacity to do so, by a march through its heart to the coast. He kept his adversaries at bay by always having alternative objectives. If the Confederates attempted to block his way to one town, he merely marched on another.

Sherman believed that the people of the South had unleashed the war on the Union and should therefore bear the consequences of their actions. “[W]e are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies.” As he had previously written to an aid worker in 1862, “War is the remedy our enemies have chosen. Other simple remedies were within their choice. You know it and they know it, but they wanted war, and I say let us give them all they want; not a word of argument, not a sign of let up, no cave in till we are whipped or they are." He was a proponent of “hard war,” pursuant to which the destruction of property in order to deprive the enemy of its use was a legitimate tactic.

One example of Sherman’s hard war has particular relevance to the war in Gaza, where urban combat has embroiled civilians in the conflict between competing armies, namely Sherman’s treatment of the city of Atlanta.

Sherman in Atlanta

Sherman’s siege of Atlanta augured the problems of urban combat that would become more frequent in the 20th century. By the time that Sherman’s forces approached the city, the Confederate lines under John B. Hood were entrenched within the city limits, intermingled with the civilian population. Shelling by Union forces inevitably hit civilian targets and, as Sherman would subsequently note in a letter to Hood, the Confederates had razed several neighborhoods in order to fortify their lines and clear their lines of fire. Ultimately, Confederate efforts were of no avail, as Sherman, through skillful maneuver designed to cut off Hood’s supplies and lines of retreat, forced the Confederates to evacuate the city with minimal resistance.

Having captured Atlanta, Sherman was already contemplating his march through the remainder of Georgia, and he had neither the inclination nor the resources to garrison, feed, and secure the city in his rear. Accordingly, he issued one of his most-discussed orders of the war: the evacuation of Atlanta’s civilian population. To anyone who wished refuge behind Northern troops, he offered food and shelter; to those who wished to head south, he offered transportation to the Confederate lines. In a letter to General Henry Halleck, Sherman outlined the military reasons for the evacuation: He did not wish to defend the entire city, including suburbs, but preferred to contract his lines; he did not want to be responsible for feeding the city; he worried that resistance would be maintained within the population, but also that his troops would be burdened by non-military matters; and, he wanted to use the houses of Atlanta for housing and storage.

Needless to say, Sherman’s order provoked outrage in the South. He received letters from Hood as well as from the mayor and city councilors of Atlanta accusing Sherman of “unprecedented cruelty.” To Hood, Sherman wrote that the Confederates themselves had displaced the population by razing houses and other buildings in their defense of Atlanta. More importantly, Sherman argued that Atlanta was “no place for families or non-combatants,” and that it would be far crueler to fight in an urban setting that was filled with unarmed civilians.

If we must be enemies, let us be men, and fight it out as we propose to do, and not deal in such hypocritical appeals to God and humanity. God will judge us in due time, and he will pronounce whether it be more humane to fight with a town full of women and the families of a brave people at our back or to remove them in time to places of safety among their own friends and people.

To the mayor of Atlanta, and certain city councilors, Sherman expounded more fully upon his concept of war. In a letter, he wrote that the evacuation was not “designed to meet the humanities” of Atlanta’s citizens, but to “prepare for the future struggles in which millions of good people outside of Atlanta have a deep interest.”

We must have Peace, not only in Atlanta, but in All America. To secure this, we must stop the war that now desolates our once happy and favored country. To stop war, we must defeat the rebel armies which are now arrayed against the laws and Constitution that all must respect and obey. To defeat those armies, we must prepare the way to reach them in their recesses, provided with the arms and instruments which enable us to accomplish our purpose.

Sherman chided the mayor and councilors for “feeling very different” when the horrors of war ravaged states other than Georgia. “You depreciate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition, and moulded shells and shot, to carry war into Kentucky and Tennessee, to desolate the homes of hundreds of thousands of good people who only asked to live in peace at their old homes, and under the Government of their inheritance.”

Sherman concluded by arguing that the most humane course would be to finish the war as quickly as possible, notwithstanding the consequences to the people of Atlanta.

You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to Secure Peace. But you cannot have Peace and a Division of our Country. If the United States submits to a Division now it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is Eternal War.

* * *

You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.

Sherman’s attitude remained constant during his march through Georgia, which he vowed to make “howl,” and then during his advance through South Carolina, a state he held particularly responsible for the war.

Lincoln and Grant

Sherman’s views on “hard war” were not outliers, but were shared by Lincoln and Grant. Initially, Lincoln had adopted a conciliatory policy toward the Confederacy, in the belief that secession was not popular with the general population of the South but had been forced upon the states by monied interests. His attitude changed as the war progressed. In 1863, Lincoln issued “General Orders No. 100: Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field,” which regulated the conduct of Union armies during the war. It authorized the use of force justified by “military necessity,” including the destruction of civilian property and the means for the enemy to continue the war. Franz Lieber, the author of these “Instructions,” believed, like Sherman, that it was more humane to take all steps necessary to end the war as quickly as possible. One article in the Instructions sets forth this principle expressly: “The more vigorously wars are pursued, the better it is for humanity. Sharp wars are brief.”

Toward the end of the war, the concept of hard war impacted the North in another way relevant to the Gaza conflict today. The government became aware of the hardships experienced by Union prisoners of war, particularly those held in the notorious camp at Andersonville. As recounted by James McPherson in his book, Battle Cry of Freedom, Lincoln came under intense pressure to secure, through exchanges, the release of those prisoners, who were known to be dying daily. Prisoners drafted petitions that were hand-delivered to Washington. The Democratic party, in its platform for presidential campaign in 1864, condemned Lincoln’s “disregard of our fellow-citizens who now are, and have long been, prisoners of war in suffering condition.”

Lincoln refused to engage in any prisoner exchanges with the Confederacy because the latter refused to consider the exchange of Black prisoners, particularly those who had been ex-slaves. As long as the South offered to exchange only white prisoners, Lincoln rejected any negotiations. Moreover, as McPherson recounts, Grant had another basis for opposing such exchanges. Grant reasoned that Confederate prisoners, “hale, hearty, and well-fed,” would promptly rejoin the fight against the Union. By contrast, the emaciated and half-starved Yankee prisoners would never be in shape to carry arms again.

It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to exchange them, but it is humanity to those left in our ranks to fight our battles.

Lincoln stood on his principle. Because the South never agreed to release Black prisoners, no major prisoner exchanges took place.

Bret Stephens Today

It is hard not to see the reasoning of Sherman, Grant, and Lincoln in Stephens’ recent column. Like Sherman, he argues that “the highest justification for fighting a war, besides survival, is to prevent its repetition.” One wonders whether a sharp war, rather than the one prolonged by Washington’s restrictions place upon Israel, would have been more humane. Similarly, Stephens, like Grant, recognizes that concern for the hostages must be balanced against the greater harm that might result from an exchange of hostages. He reminds us that Yahya Sinwar, the mastermind of the October 7th attack, was himself released as part of a hostage exchange for one Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit. Stephens further argues that, if Israel relinquishes control of the Philadelphi Corridor, along the Gazan border with Egypt, through which Hamas smuggles weapons, “Hamas will ensure that any Israeli effort to retake the corridor will be as bloody as possible, for both Israelis and Palestinians, whom Sinwar treats as human shields. Those risks, too, should weigh on the moral scales of what Israel does next.”

Stephens concludes:

Any decent human being must feel acutely sympathetic to their plight. But sympathy cannot be a replacement for judgment. Israelis — the hostage families above all — have spent the past 11 months suffering the bitter and predictable consequence of the Shalit deal, which also came about on account of intense public pressure to free him. A good society will be prepared to go to great lengths to rescue or redeem a captive, whether with risky military operations or exorbitant ransoms. Yet there must also be a limit to what any society can afford to pay. The price for one hostage’s life or freedom cannot be the life or freedom of another — even if we know the name of the first life but not yet the second. That ought to be morally elementary.

Many modern scholars criticize the tactics employed by Sherman and Grant during the Civil War. But in two instances, Sherman was indisputably correct. First, war is cruelty, and one cannot refine it. Second, if peace is achieved without eliminating the division that caused it, the result will be, as the history of the Middle East has demonstrated, that fighting “will not stop,” and the combatants will reap, if they have not already, an inevitable fate, namely “Eternal War.”

Another analogy: After the Allies scored a victory in North Africa in 1943, nobody was saying, "Gee, we've hit them back, so let's be proportionate and stop here and see if Hitler wants to negotiate a peace.""

Your post raises the tough questions that come with war. Anyone who talks lightly about "going to war" must not understand the horrors and chaos that come along with it, and you laid those out clearly in your piece. Nothing is the same after the bombs start exploding and I am always thankful that we haven't seen a war on US soil since the Civil War which, as you noted, was a terrible time for America. A visit to Gettysburg will cement that into one's brain. Your piece is a sobering read for those willing to take the time to read it. And the tragedy happening today in Gaza and other places around the world are so sad. Peace, please! Let's find peace.