Ghosts of the Hayes-Tilden Election of 1876

Last week, Special Prosecutor Jack Smith indicted Donald Trump, in Washington, D.C., for the alleged crimes of Conspiracy to Defraud the United States, Conspiracy to Obstruct an Official Proceeding, and Obstruction of, and Attempt to Obstruct, an Official Proceeding. The indictment, the third against former President Trump this year, alleges that Trump asserted claims of election fraud that he knew to be false, as a pretext to pressure selected state governments to refuse to certify electors, or to promote his own electors. The indictment further alleges that President Trump conspired to pressure Vice President Pence either to recognize Trump electors or to refer back to the states which electors to recognize. The purported legal basis for this strategy was set forth in a two-page memorandum authored by a law professor and advisor to President Trump, John Eastman, named by the indictment as a co-conspirator. That memo argued that merely disputing the electors would be sufficient to affect the election because: (1) without the disputed electors, Trump would have a majority of the remainder, or (2) if he needed a majority of all electors, the failure of both candidates to obtain a majority would throw the election to the House.

The idea of objecting to electors was not original to Trump or his advisors. In fact, prior to 2020, Democratic Congressmen, primarily members of the Black Caucus, had routinely employed this tactic. Certain Congressmen objected to the certification of Florida’s electors in 2000, when George W. Bush was first elected, on the grounds of purported voter suppression. They objected, in 2004, to the certification of Ohio’s electors, again on the ground of purported voter suppression. In 2016, Democrats objected to the certification of Donald Trump’s election on the reflexive ground of so-called Russian collusion. Thus, Democrats have objected to the certification of Republican electors in connection with every elected Republican president in the twenty-first century.

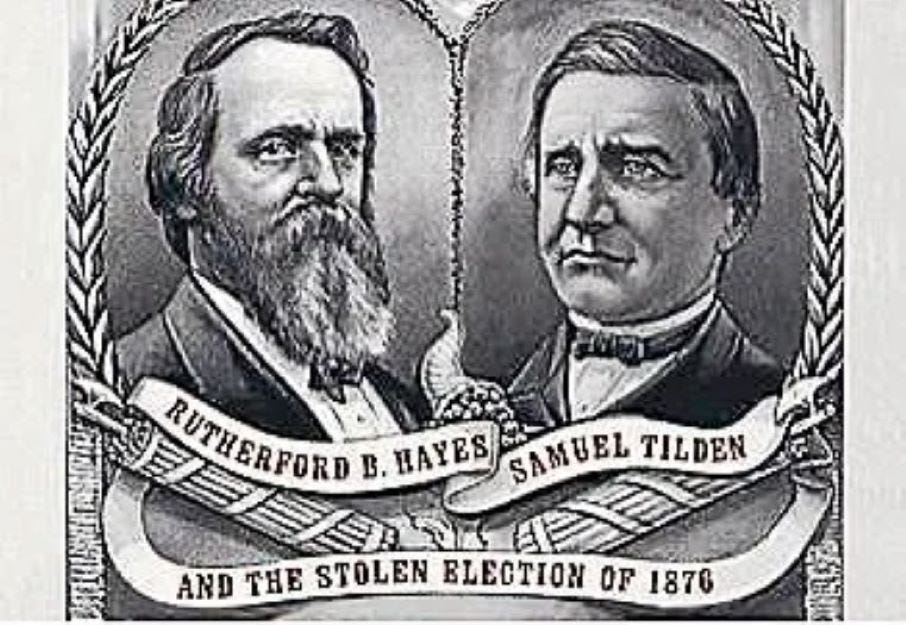

Each of these challenges involved a mere handful of legislators. There was one election, however, famous in United States history, where the electors in several states were subject to challenge, and the resolution of that challenge determined the outcome of the election. That election was the contest, in 1876, between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden.

Background to the Election

Many have referred to the events of January 6th as the greatest threat to American democracy since the Civil War. Whether or not this overstates the events of that day, it understates the danger to the country brought about by the election of 1876. At that time, the country was just little more than a decade removed from a civil war that had claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and had devastated almost half of the country. Federal troops still occupied the defeated South, and they were part of a process that would remake the political, social, and economic systems that had sustained the region for centuries.

At the time, three states -- Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana -- remained under Republican control. For example, the Governor of South Carolina, Daniel Chamberlain, was a Massachusetts Republican who had been an officer in a black regiment. As Democrats sought to “redeem” these last Southern states, serious violence, that eclipses any 2020 protest, broke out in several states. For example, in South Carolina, where former Confederate General Wade Hampton was running for Governor, armed whites attacked a local black militia in the town of Hamburg. The militiamen were cut down as they sought to escape a house where they had sought refuge. All in all, five men were executed, and another three wounded. The houses of the blacks were looted and their corpses left untended for days. The Hamburg attack was followed by further atrocities in South Carolina. As recently recounted by Ron Chernow, in his biography of Ulysses S. Grant, Grant, seventeen blacks were killed in Ellenton, South Carolina, including a black state legislator. Over the course of the summer, it was estimated that 150 South Carolina blacks had been murdered. As a result, the Governor declared a state of insurrection, and over a thousand troops were dispatched to the state to keep the peace.

Violence occurred in Mississippi as well. As recounted by Chernow, the Republican governor’s wife observed “that among the ‘principal men’ in the state capital, ‘there is hardly one who has not, by counsel or action, taken some part in the Negro murders.’” Grant was forced to send three companies of federal troops to that state, although the local U.S. Marshal had suggested that ten companies were required. Voter intimidation, or “suppression,” was so effective there that in certain counties, only one or two Republicans dared to vote.

Violence was rampant in Louisiana as well. On the weekend before election day, at least ten prominent black Republicans were beaten, whipped, or outright murdered by members of Southern paramilitary organizations such as the White League in order to intimidate blacks from going to the polls. It was in this environment that Americans went to the polls to elect either the Republican candidate, Rutherford P. Hayes of Ohio, or the Democratic candidate, Samuel Tilden of New York.

The Election of 1876

As the election results came in, it appeared that Tilden was cruising to a comfortable victory. Ahead in the popular vote by nearly a quarter of a million votes, Tilden gained 184 electoral votes, just one vote short of a majority in the Electoral College, while Hayes had 166 votes. The remaining 19 votes were in the three Southern states that still had Republican administrations – Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana. The vote count in those states would prove to be chaotic and violent.

The day after the election, a train containing officials to verify the vote count in Southern states was deliberately derailed after it left Washington. Grant was compelled to send federal troops to Florida and Louisiana to protect the vote tabulation. Threats of violence abounded. President Grant received numerous death threats and ordered troops to Washington to ensure that peace was kept. In South Carolina, Democrats invaded the state legislature, installing their own speaker and clerk. Grant refused to use federal troops to reinstate the Republican legislature. Both Chamberlain and Wade Hampton declared themselves to be the lawfully elected Governor.

Similar chaos enveloped Louisiana. Democrats there similarly besieged the state legislature. There were two legislatures, one Republican and one Democrat, each of which claimed to have been lawfully elected. Representatives of Grant sent to inspect the vote count in that state, which included Senator John Sherman, the famous general’s brother, and future President James Garfield, found that widespread fraud and voter intimidation had occurred.

Notwithstanding these irregularities, or because of them, many historians believe that Tilden clearly won the popular vote in Louisiana, probably won the vote in Florida, and possibly won the vote in South Carolina. Victory in even one state would have been sufficient for him to secure election. On the local level, the votes were initially tabulated by precinct and county officials. These results were then reviewed by state canvassing boards. In Louisiana, Tilden had large leads in the vote tallies compiled by the local officials. However, the state canvassing board, controlled by Republicans, disallowed more than 13,000 Tilden votes, paving the way for Hayes to be declared the winner. Citing systematic intimidation, murder and violence toward Republican voters, black and white, the canvassing board threw out the votes of two parishes in their entirety, as well as sixty-nine partial returns from other parishes.

Canvassing boards in South Carolina and Florida engaged in similar tactics to lower the Tilden vote, although in South Carolina, Hayes appeared to have won the vote as tabulated by the local officials. The final state to report was Florida, where officials recognized that their determination would decide the election. In Florida, the canvassing board overlooked several irregularities, including the receipt of 219 votes after the polls had closed. While their conduct was not as extreme as it was in Louisiana, it was sufficient to put that state in the Hayes column.

As a consequence, the election results in three states -- Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana (one elector was subject to challenge as well in Oregon) – were hotly disputed. The dueling legislatures in each state submitted for certification two sets of electors. Thus, the country was faced with the unprecedented spectacle of an election where the electoral vote tally was in dispute.

The Resolution of The Conflict

The resolution of the dispute was now thrust upon Congress. The critical issue remained: who was to count the vote? Democrats, who had a majority in the House, pointed to Article II of the Constitution, which provided that if no candidate achieved a majority of the electoral votes, the President was to be chosen by the House, with each state delegation getting one vote. Republicans relied upon the Twelfth Amendment, which provided that the President of the Senate, i.e., the Vice President, “shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.” It was upon this same language that Professor Eastman relied when advising President Trump that Vice President Pence could determine which set of electors was validly elected. Other proposals included suggestions that the House and Senate vote, either together or independently, or that the Supreme Court decide.

When Congress met after the election, the parties disputed the appropriate way to determine the winner of the election. However, many Republicans and Democrats alike realized that any of the above procedures would taint the winner irrevocably. Accordingly, a Republican Senator from Iowa introduced a resolution for the creation of an electoral committee, “whose authority none can question and whose decision all will accept as final,” to study how to determine the winner. The House passed a similar resolution, whereupon the two committees worked together to create an electoral commission to decide the outcome of the election.

The composition of the Commission took further time to sort, but it was determined that it would contain fifteen members, five chosen from the House, five chosen from the Senate, and five chosen from the Supreme Court. As the Democrats held the House, three of its Commission members would be Democrats. As the Republicans controlled the Senate, three of its members would be Republican. Four of the members from the Court would be chosen along party lines. This left the fifteenth, and probably deciding vote, to be filled by an independent Justice decided by the other four. Initially the choice was presumed to be Justice David Davis of Illinois, who had been a Republican and a close associate of Abraham Lincoln but who, in the words of a fellow member of the Commission, writing for the Atlantic magazine decades later, subsequently “belonged to a highly respectable class of politicians known as Independents.”

It was said of him there, no doubt with some jocose exaggeration, that he seemed to be trying to divide his influence, his voice, and his vote, as equally as possible between Democrats and Republicans; that if he voted twice in succession with the same party, he appeared to be alarmed lest he should take on the character of a partisan, and made haste to restore the healthful balance of his mind and of his political action, by voting next time with the other side.

Unfortunately, demonstrating his bipartisanship, the former Republican accepted the Democratic nomination in Illinois for the Senate, disqualifying him from selection to the Commission. As a backup, the four Justices chose Justice Joseph P. Bradley, a conservative Republican from New Jersey. Davis was acceptable to many Democrats as he had served as a jurist in Louisiana, where he had intervened to free defendants who had participated in the Colfax Massacre, wherein members of the White League had slaughtered up to more than 150 black militiamen. His decision was ultimately upheld by the full Supreme Court, which determined that the protections of the 14th Amendment applied only to government action, not to that of private citizens. The Democrats’ acceptance of Justice Bradley would not survive the work of the Commission.

That work soon devolved to the resolution of one issue: Should, as Republicans urged, its members accept the official certification of the canvassing boards and declare Hayes the winner? Or, as Democrats urged, should the Commission look beyond such determinations and address such issues as fraud to determine the true facts of the case. The enabling statute only gave the Commission the same power as Congress to count the vote, so the answer to the issue was ambiguous. Ultimately, Justice Bradley came down on the side of Republicans, and Hayes was declared the winner by the Commission. The margin of victory was one vote.

The statute that created the Commission stated that its determination could only be set aside by a vote of both houses of the legislature. With Republican control of the Senate, this would never happen. Democratic legislators attempted to filibuster the vote in order to delay the election. Further, when the House and Senate considered a separate challenge to one elector from Wisconsin, which, if successful, would leave neither candidate with a majority, a Texas Representative moved to have the House exercise its powers under Article II to select the President, a motion that presaged a strategy set forth by Professor Eastman almost 150 years later.

Ultimately, Hayes was elected President. Many historians suggest that the final resolution of the election was the result of an agreement between Hayes and the Democrats to withdraw federal troops from the South and to end Reconstruction. Whether or not this is true, it is irrelevant to the outcome of the election.

Deciding Elections Today

In 1887, Congress attempted to resolve many of the issues it had confronted ten years earlier by the passage of the Electoral Count Act. That act placed many of the responsibilities for determining the validity of electors on the states. That act was further amended after the last election to make clear that the Vice President’s role in counting the electors is purely ceremonial. However, many of the issues raised in the 1876 election remain relevant today, particularly with respect to the third indictment.

As set forth above, many of the legal theories set forth by Professor Eastman, characterized as components of a criminal conspiracy by the indictment, were initially articulated almost 150 years ago. First, the idea to challenge electors was not originated by Professor Eastman. It was Democrats who made such challenges routine over the past two decades. Second, long before Professor Eastman, Republicans argued in 1876-77 that the Vice President was the sole person authorized by the Constitution to choose between two conflicting slates of electors. Third, it was Democrats who argued in 1876-77 that Congress could look past the state certified election results, just as Professor Eastman did, to determine whether fraud had occurred. To the extent that the latter issue was addressed by the Electoral Count Act, Professor Eastman is not the first to argue that such statute is unconstitutional. Indeed, almost since its enactment, many commentators have questioned whether the Electoral Count Act passes constitutional muster, or whether it can bind a Congress that always has the power to revise the rules through which it exercises its Article II powers.

One can agree (as this writer does) that Professor Eastman’s advice was both dangerous and wrongheaded, premised as it was upon a record that contained, at best, little evidence of outcome-determinative fraud. Even in an environment far more heated and charged than that today, enough Republicans understood that to allow one man, particularly one whose office was affected, to decide the outcome of an election would provoke a constitutional crisis, even if there was strong evidence of electoral fraud. One can also agree with Jack Smith (as this writer does) that the threat posed by President Trump’s attempt to game the Electoral College was far greater than any threat posed by the riot at the Capitol on January 6th, and that this threat should disqualify him from ever holding office again.

It is another thing altogether to assert that holding these ideas is criminal. As many commentators have observed, politicians, Democrat and Republican alike, routinely effect legislation or election based upon assertions that they know to be either factually wrong, or legally incorrect. To criminalize such conduct sets a precedent that itself threatens the orderly functioning of democracy. Unfortunately, it likely will be left to the Supreme Court to decide that issue, whereupon politicians will inevitably label the Court illegitimate and not “normal.” Perhaps that is precisely the point.