Hello, I Must Be Going: Another Time A New Candidate Emerged 3 Months Before An Election

It is hard to believe that former President Donald Trump’s assassination attempt happened less than two weeks ago. Since then, Trump has both chosen his Vice Presidential pick in Ohio Senator J.D. Vance and made his first public appearance since the shooting at the Republican National Convention.

However, what has arguably taken up even more print space during these past few days has been President Biden’s decision to decline the Democratic nomination for president and instead endorse Vice President Kamala Harris.

But this is not the first time a new candidate has suddenly had to face an election with only three months to go. Exactly forty years ago, a similar situation played out north of the (American) border.

Reading the Snowflakes

On February 29th, 1984, Pierre Trudeau gave notice that he was resigning as Prime Minister after nearly 16 years in the job. The move was not entirely surprising; the Great White North was struggling with “stagflation,” a combination of inflation and unemployment, and the populace had tired of the decades-long reign of Trudeau and his party. It seemed likely that he would be forced out – fewer than 20% of people surveyed believed that Trudeau was the best man for Canada’s prime minister.1

It may have been pondering such dismal numbers during his infamous “walk in the snow” that spurred Trudeau to resign the next day, on leap day no less. Though the move was not entirely shocking, it nevertheless took both aides and the population at large by surprise. It was hastily made – Trudeau himself had often bragged that he tended to make all his decisions within 48 hours.

Instead of holding a news conference to announce his resignation, he hand-delivered a letter to Iona Campagnola, the then-president of his Liberal Party. Campagnola, in turn, later read the letter aloud to a televised audience that afternoon. This in itself caused some controversy; as noted by The New York Times at the time, “his decision not to hold a news conference led to accusations by some Canadian journalists that, in departure as in office, he showed disdain for reporters and Members of Parliament.”2

Trudeau’s resignation accordingly set off a flurry of who would become the next leader of the party, which was to be decided later that June at the national convention. This new leader, in turn, would be the party’s candidate for Prime Minister in the following election. According to Canadian law, an election was required by that spring, but public and Parliamentary pressure made it inevitable that the government would call for an election that fall.

A New Candidate

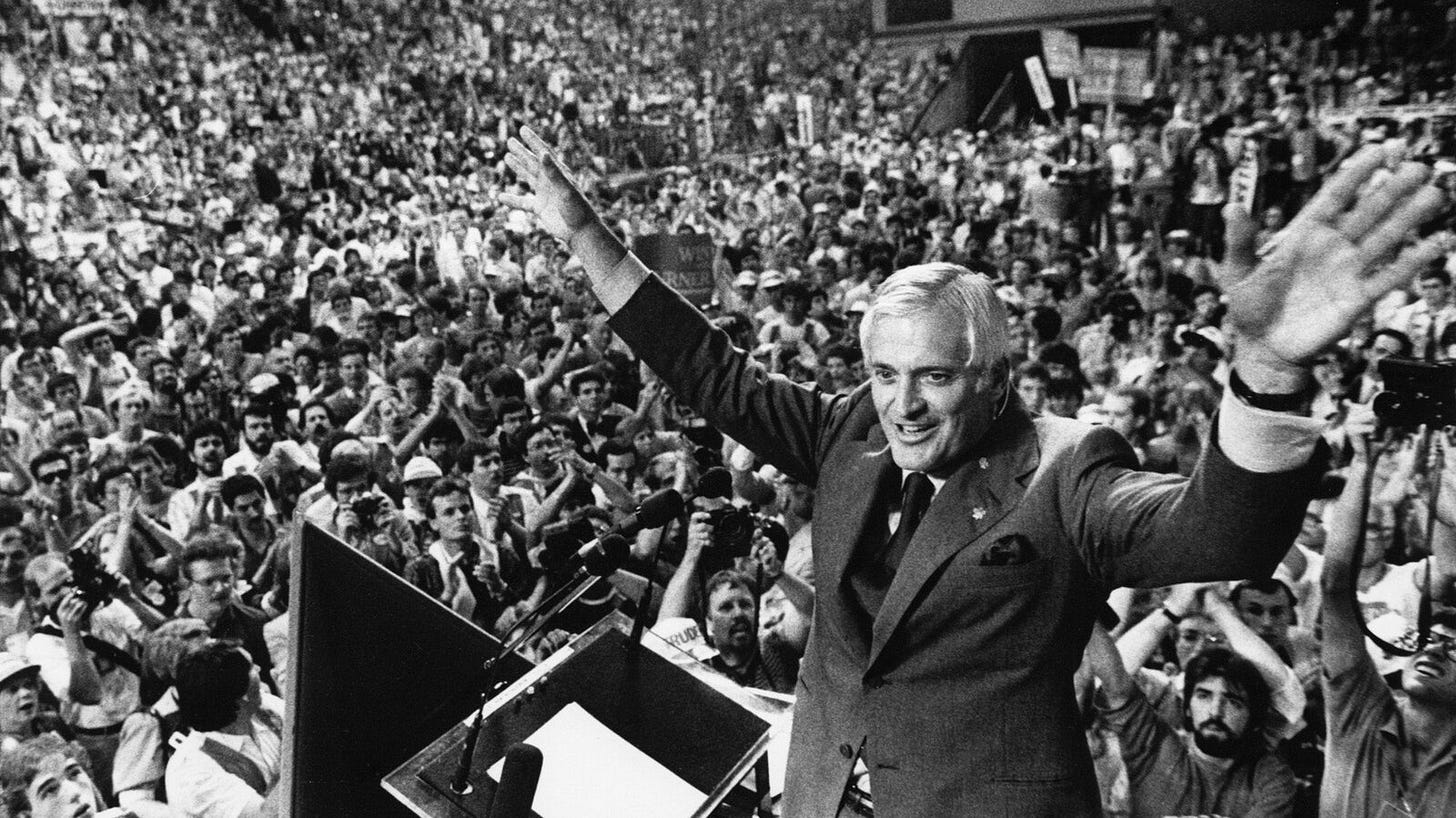

The immediate front-runner was John Turner. Turner was an accomplished candidate; he was a Rhodes scholar, a runner who held the Canadian record for the men’s 100 yard dash (a knee injury prevented him from competing in the Olympics), and a corporate lawyer before turning his hand at politics. He served as both the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Justice Attorney General (yes, that is all one title) under Trudeau. This was the description given of him by Walter Stewart:3

“In appearance, he is perfect. Looking for the man to play the senator from Rocky Ridge, central casting would bring him into the part without hesitation . . . He has the voice, the carriage, the manners, the polish, the brains. He is bilingual, charming, and hardworking. He chats as easily with tycoons as with janitors, smiles a lot, laughs a lot, and is guaranteed not to fade, rust or drip on the carpet.”

That is not to say that Turner did not have his drawbacks. He had found himself at loggerheads with Trudeau at various points, even resigning his position to return to corporate law for 8 years. Moreover, despite the above description calling him “charming,” most other accounts have described him using terms such as awkward and disingenuous. One author claimed that he spoke like a “corporate manager.”

But these set-backs did not stop him from winning the position of Prime Minister following a brief internal party struggle. The next task was keeping his position for the general election three months away.

Immediately, Turner faced a major predicament. As summarized by The Big Red Machine: How The Liberal Party Dominates Canada’s Politics by Stephen Clarkson:

“Turner and his strategists had still not resolved the conundrum of how to accommodate the Trudeau legacy and at the same time turn the public’s desire for change to his own advantage. His key advisers wanted him to swing back to the right and appeal to the West. Yet if he ran against his own party’s record in government, the danger was that the voters might agree and reject the Liberal Party lock, stock, and barrel.”

With only three months until the election, Turner and his team did not have time to clarify their vision, and the inability to walk the line between change and continuity led to a vague message and speeches with decidedly “weak content.”

As again noted by The Big Red Machine:

“Although Torrance Wylie, Senator Michael Kirby, and Tom Axworthy, three policy wonks from the Trudeau era, were hastily recruited to produce solid theme texts for the leader’s use, their material arrived late and was so inadequate that Turner’s scripts were mainly produced on his plane by one staff person scribbling valiantly without research support. A large youth-apprenticeship program; grants for young entrepreneurs; a doubled tax write-off for capital losses; a tax credit for living in the North . . . it was a scattershot production that did nothing to clarify the confusing personal message that Turner was transmitting through his own performance.”

But Turner was not particularly worried about his own lack of message, especially since he considered his opponent, Brian Mulroney, an unserious candidate: “[Turner] held Brian Mulroney in low regard, deeming him as lightweight in politics as he had been in business. When offered the choice between the untried Mulroney and the experienced Turner, surely the public would choose the better man.”

Turner was convinced that Mulroney would make a serious misstep, but “in waiting for Brian Mulroney to self-destruct, Turner lost control of the political agenda and let the media concentrate on the mistakes, small and large, with which he proceeded to oblige them.”

Ironically, Turner was the one to make two gaffes that defined the election. The first was when a camera caught him placing his hand on Iona Campagnola’s posterior, a move that enraged much of his female base. But the biggest one was during a debate with Mulroney. Turner defended continuing Trudeau’s plush appointments by saying he had “no option.” “You had an option, sir. You could have said no,” was Mulroney’s reply.

Turner and his party went on to suffer one of the worst defeats in Canadian history.

From Canada to Kamala

Though rarely are comparisons perfect, it is hard not to see the similarities in Trudeau/Turner and Biden/Harris today. Like Trudeau, Biden dropped out suddenly, giving his successor little time to craft a plan before an election – moreover, they did so without announcing with a traditional press conference, perhaps highlighting their unhappiness at stepping down and consciousness about their unpopularity.

Harris, like Turner, is facing a country that is bogged down with economic issues. Though the United States has avoided stagflation due to tight unemployment rates, many pundits are pointing out that the unemployment numbers are abetted by government jobs instead of free market ones, muddying the waters on true economic data. Less murky is the fact that most Americans are struggling with the high prices brought on by inflation; around three quarters of Americans have claimed that strengthening the economy is their top priority in 2024.4

Harris, like Turner, has the predicament of not alienating the traditional Democratic base, especially in rust and sun belt states, while trying to differentiate her policies from the unpopular Biden-era ones. Also like Turner, Harris’s public comments can swing from win to loss. At times, she appears confident and composed (e.g. the “that little girl was me” line from the 2020 primary debate). During others, she has been caught in bizarre and blatant lies (e.g. the Lester Holt “I visited the border” interview) or simply babbles nonsensically (e.g. the “coconut tree” remarks). Moreover, it seems as if Harris and the Democratic machine are betting on missteps from the Trump team that might not come, especially as Trump is clearly adapting his campaign to avoid his previous weaknesses.

But this race is far from over. Unlike Turner, who allowed the short three month period before the election to stifle his message, Harris still has the ability to refine her vision. Her early campaign videos do not seem promising — focused mainly on abortion and vague “human rights” — but it has not yet been a week since Biden bowed out.

That said, Harris also has weaknesses that Turner did not; in particular, her disastrous handling of the border will likely come to haunt her, which is perhaps why so many media outlets are attempting to rewrite history and deny her association with the issue.

Moreover, Donald Trump is not Brian Mulroney, and has both his ardent fans and haters which will possibly impact the race far more than opinions on Harris. The media, too, is a third player in the race, and are already rehabbing her image in a way that was alien to politicians on both sides of the aisle of yore.

Nevertheless, history has shown that a leader exiting a race shortly before an election bodes poorly for the politician holding the bag. It remains to be seen how Harris and her team will manage to avoid this fate.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3790958?origin=crossref

https://books.google.com/books?id=pC3wqzDBlCcC&pg=PA101&lpg=PA101&dq=%22Looking+for+the+man+to+play+the+senator%22&source=bl&ots=wTRqUF08J2&sig=ACfU3U2a16QQT4KjnPSQsLMJ8W8zHMyNhQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiAn7Gt6MSHAxUKFlkFHVRLAAAQ6AF6BAgTEAM#v=onepage&q=%22Looking%20for%20the%20man%20to%20play%20the%20senator%22&f=false

https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/02/29/americans-top-policy-priority-for-2024-strengthening-the-economy/#:~:text=16%2D21%2C%202024%2C%20among,citing%20any%20other%20policy%20goal.

B.D. Mulroney Aug. 5

A.H. Childs’s description of Turner and particularly of his gaffes during the 1984 Canadian election rings true. While his awkward campaign certainly did not help, the 1984 election was probably not winnable for the Liberals from the start.

In the fall of 1976, the Parti Quebecois managed a shocking victory in the Quebec provincial election. Party leader Rene Levesque had campaigned largely on a promise to stage a referendum on whether the province should separate from Canada.

The historic background to 1976 is long and complicated but certainly includes Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s pan-Canadian view of Quebec language and culture, exemplified by passage of the Official Languages Act of 1968 as well as his handling of the “October Crisis” generated by the Front de libération de Quebec (FLQ) kidnapping of British Trade Commissioner James Cross and Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte. To deal with the crisis, Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act, resulting in the summary arrest and detention of hundreds of Quebec professors, trade unionists and artists who, while they may have supported independance, had little or no connection to the FLQ.

Levesque made good on his promise to hold a referendum. Quebecois voted in late 1980. Earlier that year Trudeau, seeking to reclaim power after a brief spell in opposition in 1979, promised Quebecois that if they voted to remain in Canada, he would “patriate” the Canadian constitution. At the time, the statutory part of Canada’s constitution was an act of the U.K. parliament, the British North America Act of 1867. Trudeau promised to enact a more modern Canadian version, including a Charter of Rights and Freedoms (equivalent to the U.S. Bill of Rights). Most importantly, he promised that he would consult the provinces on the composition of the documents and that the legislation would be subject to unanimous provincial consent. After two years of exhaustive negotiations, all provinces other than Quebec had reached a deal. Quebec’s outstanding issues were not ones that the other nine provinces and the federal government could accept. Trudeau chose to proceed without Quebec consent. He, and the Liberals, were anathema to Quebec from that point on.

Canadians do not vote for Prime Minister in their federal elections. They vote for a local Member of Parliament. The leader of the party that elects a plurality of MPs becomes Prime Minister. It is almost impossible to win a federal election without a fair number of seats in Quebec. In 1980 the Liberals had won 74 Quebec seats, virtually all of the seats in the province. The 1984 election saw their seat total in Quebec reduced to 17. The Liberals lost seats in Ontario as well, but Quebec’s emphatic rejection of the party was the principal reason for their loss.

Mulroney was born in small-town Quebec and spoke Quebec French fluently. He was witty, personable and a fierce debater. Many regard him as one of Canada’s greatest Prime Ministers. He and Turner faced off again in the “Free Trade” election of 1988. Mulroney won, but much more narrowly than he had in 1984.

Interesting article. Mulroney turned out to be an excellent Prime Minister. In the modern era, Vice Presidents have a tough time succeeding the Presidents they serve. Nixon failed in 1960, Humphrey in 1968, Mondale in 1984, and Gore in 2000. It's hard making yourself appear fresh when you need to defend the Administration you were part of, but not responsible for. The exception is George H.W. Bush in 1988. But Bush followed an unusually popular and successful President Reagan, while facing a weak opponent in Michael Dukakis. Harris, by contrast, is forced to defend the unpopular Biden Administration--from inflation to the border to the Afghanistan withdrawal, although in Trump she faces highly divisive and unpopular opponent. It's Trump that gives her a chance.