The Wall Street Journal recently ran a piece, The Protesters Make the Case for Zionism, that was of particular interest to me. Several months ago, I wrote the preliminary draft of a similar piece, after discussions with charter subscriber Jonathan Dorfman. I had hoped to be the first to raise the argument, but because H,R,& R had written so much about the Israeli conflict in Gaza at the time, I shelved it for later, only to be beaten to the punch. Clearly, it was not my time, and instead of a shot at a national publication, I got the proverbial one-way ticket to Palookaville.

Nevertheless, because I think I have something to add to the discussion, because the issue of antisemitism continues in this country, and, more personally, because I am not going to waste an article I have already written, I am picking up the cudgel on this subject, even though second to the party.

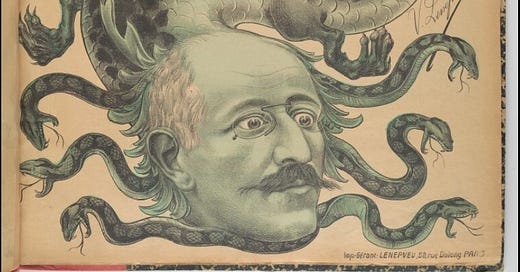

Antisemitism in this country has erupted in ways that is shocking to many, particularly to those for whom the Holocaust is not a tale portrayed in history books, but something far more immediate. Crowds throughout America have openly called for the elimination of Jews either implicitly “(From the river to the sea,” “There is only one solution.”) or explicitly ("Al-Qassam's next targets."). This ethnic hatred has been rationalized by apologists for the protesters by the thesis that the protesters are not antisemitic, but anti-Zionist. Assuming this rationalization to be well-intended, the question remains to what extent the two can be separated, or whether the dichotomy is a false one. As the early Zionists argued, Zionism is the inevitable consequence of antisemitism. Without the former, the latter would not exist. Indeed, many of the early Zionists, including Theodor Herzl, espoused assimilation before turning to Zionism. Herzl argued that Christian Europe should encourage assimilation, because assimilation and prosperity were the likeliest factors to erase a separate Jewish identity. (“[The world] fails to observe that prosperity weakens our Judaism and extinguishes our peculiarities.”). However, these Zionists came to the conclusion that Jews would never be allowed to become members of Christian society, but would always be regarded as outsiders. It is remarkable how timely their criticisms are today.

The Zionists’ Case

As the Journal article suggests, most people argue that the foundational document of the Zionist movement is a short book written by Theodore Herzl, entitled Den Judenstaat, or the Jewish State. The book was written in 1895 and published in 1896, at or about the time of the Dreyfus Incident, where a French-Jewish officer, falsely accused of supplying secrets to the Germans in 1894, was tried for treason, convicted, and exiled to Devil’s Island. Thereafter, as new evidence came to light exonerating him and demonstrating the injustice of his trial, numerous public figures, including, most famously Emile Zola, called for a new trial. Dreyfus was given such a new trial in 1896, but, despite the new evidence, was convicted again. He was almost immediately pardoned, but would not be formally exonerated for another decade.

While Den Judenstaat was written after the first Dreyfus trial, and while Herzl was unquestionably influenced by the events in France, Dreyfus, contra the Journal, was not necessarily the catalyst for the Zionist movement or even for Herzl’s penning Den Judenstaat. Other early Zionists, had “awakened to their Jewish origins” and “come to the conclusion” that Jews needed their own homeland long before 1894, and Herzl, based upon his own contemporary writings, appears to have come to Zionism based upon other factors.

As noted in our article, The Two-State Two-Step – Israel’s Century-Long Dance Marathon, or Why Joe Biden Thinks He Can Succeed Where Winston Churchill Failed -- PART I, Zionism emerged as an informal movement in Europe in the late 19th century, but accelerated after first, the Odessa pogrom of 1871, and then the assassination of Russia’s Czar Alexander II in 1881, precipitating numerous further pogroms in Russia, particularly in Odessa, which were followed by the passage of the May Laws directed at Jews. The situation in Russia was the catalyst for the First Aliyah, regarded as the first major wave of Jewish settlers to be part of the Zionist project. This wave was so significant that, as early as 1881, the Ottoman Foreign Ministry had created a file, “Situation of the Jews; Question of their Immigration into Turkey: 1881.”

Long before the Dreyfus trial, in 1882, a Russian Jew from Odessa, Leon Pinsker, had penned a pamphlet calling for the establishment of a Jewish homeland. Originally an assimilationist who advocated for the secular education of Jews, Pinsker had been horrified by the Odessa pogroms of 1871 (when the term pogrom was first coined in the West) and 1881, which were believed to be the first pogroms to be orchestrated by the Tsarist government. In 1882, Pinsker published, in German, a pamphlet entitled “Auto-Emanzipation. Ein Mahnruf an seine Stammesgenossen. Von einem russischen Juden,” or (“Auto-Emancipation. A Warning Addressed to His Brethren. By a Russian Jew.” The pamphlet advocated many of the positions that would later be included in Den Judenstaat.

From the outset, the pamphlet argued that, although the original Jewish state had been crushed by the Romans, and “the Jewish people had ceased to exist as an actual state, as a political entity, they could nevertheless not submit to total annihilation -- they lived on spiritually as a nation.” For this reason, “Jews comprise a distinctive element among the nations under which they dwell, and as such can neither assimilate nor be readily digested by any nation.”

“The Jewish people has no fatherland of its own, though many motherlands; no center of focus or gravity, no government of its own, no official representation. They home everywhere, but are nowhere at home. The nations have never to deal with a Jewish nation but always with mere Jews.”

Pinsker wrote that this unique status of the Jewish nation was at the heart of antisemitism or “Judeophobia.” He argued that antisemitism had gained legitimacy, had been passed from generation to generation for two thousand years, and was incurable. In words that could be inscribed on the walls of the United Nations General Assembly, Pinsker declared:

“In this way have Judaism and Anti-Semitism passed for centuries through history as inseparable companions. Like the Jewish people, the real wandering Jew, Anti-Semitism, too, seems as if it would never die. He must be blind indeed who will assert that the Jews are not the chosen people ,the people chosen for universal hatred. No matter how much the nations are at variance in their relations with one another, however diverse their instincts and aims, they join hands in their hatred of the Jews; on this one matter all are agreed.”

Anticipating Herzl by more than a decade, Pinsker wrote that until the nations achieved the age of “universal harmony,” one which they had never achieved and were unlikely to achieve in the foreseeable future, Jews would never be safe. He determined that the only solution for the Jewish people was to establish their own homeland, to reestablish themselves as a “living nation.”

Pinsker’s Zionism was not based upon a desire to return to or to restore the Holy Land. He did not necessarily believe that the national home should be in historic Israel. Pinsker’s motivation was far more pragmatic – he was concerned with the legal and social rights of Jews and, of greater importance, their personal safety. For this reason, he advocated settlement in any land, including one in South America.

“If we would have a secure home, give up our endless life of wandering and rise to the dignity of a nation in our own eyes and in the eyes of the world, we must, above all, not dream of restoring ancient Judaea. We must not attach ourselves to the place where our political life was once violently interrupted and destroyed. The goal of our present endeavors must be not the "Holy Land," but a land of our own. We need nothing but a large tract of land for our poor brothers, which shall remain our property and from which no foreign power can expel us. There we shall take with us the most sacred possessions which we have saved from the ship-wreck of our former country, the God-idea and the Bible. It is these alone which have made our old fatherland the Holy Land, and not Jerusalem or the Jordan”.

Pinsker’s pamphlet inspired Jewish students in Vienna, including Nathan Birnbaum, who formed an overtly Zionist student organization, Kadimah, that opposed assimilation. Birnbaum, widely credited with first coining the term Zionist, published a brochure entitled Die Nationale Wiedergeburt des Juedischen Volkes in seinem Lande als Mittel zur Loesung der Judenfrage (“The National Rebirth of the Jewish People in its Homeland as a Means of Solving the Jewish Question”), in which he also anticipated many of the subsequent ideas expounded by Herzl, who also lived in Vienna.

The issue of assimilation was a significant one at the time in Vienna, as Jews in the Habsburg empire, who had only recently been emancipated and permitted to leave the ghettos, had flocked to the Austrian capital, comprising 9% of the population by the 1890s. This had prompted a political backlash, exemplified by the Christian Social Party, led by the notorious antisemite Karl Lueger, whom Adolf Hitler claimed as an inspiration. It was Lueger’s election as Mayor of Vienna in 1895, initially blocked by Emperor Franz Joseph, that many believe to have converted Herzl who, like Pinsker was originally an assimilationist, to Zionism. Herzl’s diary at the time demonstrated deep concern for events in Vienna, but mentioned the Dreyfus affair only sparingly (seven times in over 1600 pages). Indeed, in a letter to a friend, Herzl wrote that the inspiration for a play that he wrote, The Ghetto, which was his first step on the road to his embrace of Zionism, occurred before the arrest of Dreyfus.

That is not to say that the initial Dreyfus trial did not play its part or that it was not particularly shocking to Herzl. He was acutely aware of the pogroms in Russia, and considered Germany to be the homeland of antisemitism. The treatment of Jews was far milder in France than in those, and other countries. As he later wrote in Den Judenstaat:

In Russia, imposts are levied on Jewish villages; in Rumania, a few persons are put to death; in Germany, they get a good beating occasionally; in Austria, anti-Semites exercise terrorism over all public life; in Algeria, there are traveling agitators; in Paris, the Jews are shut out of the so-called best social circles and excluded from clubs.

At the same time, however, this milder attitude toward Jews is what made the Dreyfus affair so shocking. France, in contrast to other countries, was secular, cosmopolitan, and had emancipated Jews a century before during the French Revolution. If the virulent antisemitism on display could occur in France, it could occur anywhere.

Herzl’s book, completed in 1895, became even more timely at the time of Dreyfus’s second trial in 1896, when it became clear that he was innocent. The antisemitism on display became an issue of national debate, exemplified by Emile Zola’s famous polemic, “J’Accuse.” In it, Herzl expounded on many of the themes set forth by Pinsker in Auto-Emancipation.

First, like Pinsker, Herzl recognized the ubiquity and insoluble nature of antisemitism.

The Jewish Question still exists. It would be foolish to deny it. It is a remnant of the Middle Ages, which civilized nations do not even yet seem able to shake off, try as they will. They certainly showed a generous desire to do so when they emancipated us. The Jewish Question exists wherever Jews live in perceptible numbers. Where it does not exist, it is carried by Jews in the course of their migrations. We naturally move to those places where we are not persecuted, and there our presence produces persecution.

Like Pinsker, Herzl perceived antisemitism to be rooted in Jews’ status as a distinct element within the nation in which they lived:

I think the Jewish Question is no more a social than a religious one, notwithstanding that it sometimes takes these and other forms. It is a national question, which can only be solved by making it a political world-question to be discussed and settled by the civilized nations of the world in council. We are a people—one people.

Like Pinsker, Herzl came to the realization that assimilation would ultimately fail, and that Jews would never be accepted as equals in European society, but would always be deemed to be outsiders:

We have honestly endeavored everywhere to merge ourselves in the social life of surrounding communities and to preserve the faith of our fathers. We are not permitted to do so. In vain are we loyal patriots, our loyalty in some places running to extremes; in vain do we make the same sacrifices of life and property as our fellow citizens; in vain do we strive to increase the fame of our native land in science and art, or her wealth by trade and commerce. In countries where we have lived for centuries we are still cried down as strangers, and often by those whose ancestors were not yet domiciled in the land where Jews had already had experience of suffering.

* * *

We might perhaps be able to merge ourselves entirely into surrounding races, if these were to leave us in peace for a period of two generations. But they will not leave us in peace. For a little period they manage to tolerate us, and then their hostility breaks out again and again. The world is provoked somehow by our prosperity, because it has for many centuries been accustomed to consider us as the most contemptible among the poverty-stricken.

Like Pinsker, Herzl believed that no government could guarantee the safety of Jews (“[T]he statesman who would wish to see a Jewish strain in his nation would have to provide for the duration of our political well-being; and even a Bismarck could not do that.”), and that such safety could only be achieved “by means of the ultimate perfection of humanity.”

Accordingly, Herzl came to the conclusion that the only way for Jews to survive as a nation was for them to have their own homeland. Emigration was inevitable.

It is useless, therefore, for us to be loyal patriots, as were the Huguenots who were forced to emigrate. If we could only be left in peace. . . . But I think we shall not be left in peace.

Like Pinsker, Herzl was motivated by the safety of his people, not by a return to historical Israel. In Den Judenstaat, Herzl expressly posited Argentina as a potential destination for the Zionists. Subsequently, he negotiated with Winston Churchill for land in colonial Uganda, a negotiation thwarted by the opposition of British colonialists there. Even with respect to Israel, Herzl initially sought settlement, not in the holy places such as Jerusalem, but in the wasteland area of the Negev, which was far more thinly populated. Others in the movement brought him around.

Zionism Today

As I wrote in the post Never Again (Well, Hardly Ever), it seemed unthinkable, in the decades immediately following World War II, after true horrors of the Nazi regime had been revealed, that the virulent antisemitism that existed throughout history would ever be repeated. If “Never Again” lacked any currency, it was because almost no one not Jewish seriously believed that “Again” was even a remote possibility. However, while I could not have predicted the current manifestation of antisemitism, Theodor Herzl could have. As he wrote, more than a century and a half ago, “the longer anti-Semitism lies in abeyance the more fiercely will it break out.”

It is the very insecurity of Jews in greater society that was the catalyst for the Zionist movement. Today, it can hardly be argued that Jews do not live in a comparably threatening environment, where the Mayor of Copenhagen advises citizens not to wear items of clothing that identify them as Jews, where Jews in France are specifically targeted for violence, and where synagogues in the United States are forced to hire security guards and train their congregations in anticipation violent attacks. Just as Herzl was struck by the anomaly of cosmopolitan and secular France descending to virulent antisemitism, so is it striking how antisemitism has flourished among secular and cosmopolitan university students here in America. It is remarkable that Benjamin Disraeli could serve as Prime Minister of England at or about the period that spawned the Zionist movement, yet Josh Shapiro cannot be nominated for Vice President today. It is even more remarkable, that across college campuses today, students celebrate heinous acts committed against Jews.

The sentiments expressed by “activists” around the country today are the very sentiments that prompted the formulation of Zionism in the first place. Acceptance of Jews seems no closer to fruition than it did in Herzl’s day. If these “activists” were truly opposed to Zionism, they would aggressively fight the antisemitism that made Zionism necessary, rather than exacerbating it.

John, Nicely done. Ed Woodhouse '75

The old saw: Israel is for people who think Herzl was right; America is for people who think Herzl was wrong. Having lived through what has been called The Golden Age of American Jewry— an era that ended for me on October 8–Americans need to rethink their assessment of Herzl. Maybe he was right—even for Americans. Excellent piece.