Happy Mother’s Day! As a thanks to all our readers, our humble Substack is delivering the gift that every mother truly desires: an analysis of Bismarckian tariff policy and its similarity to the actions of the Trump administration.

Okay . . . we jest. But in all seriousness, a look into the history of tariffs is surprisingly fascinating because the conventional wisdom surrounding tariffs appears to have turned on its head following the end of World War II. For weeks, the media and financial elite have sounded the alarm on how tariffs are always a negative force on financial growth, citing analyses from 1945 and beyond showing how tariffs were a net drag on the economies that employed them. But those same analyses will also show that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tariffs seemed to have the opposite effect and were a net positive, creating what is known as the tariff-growth paradox (or the Bairoch hypothesis).

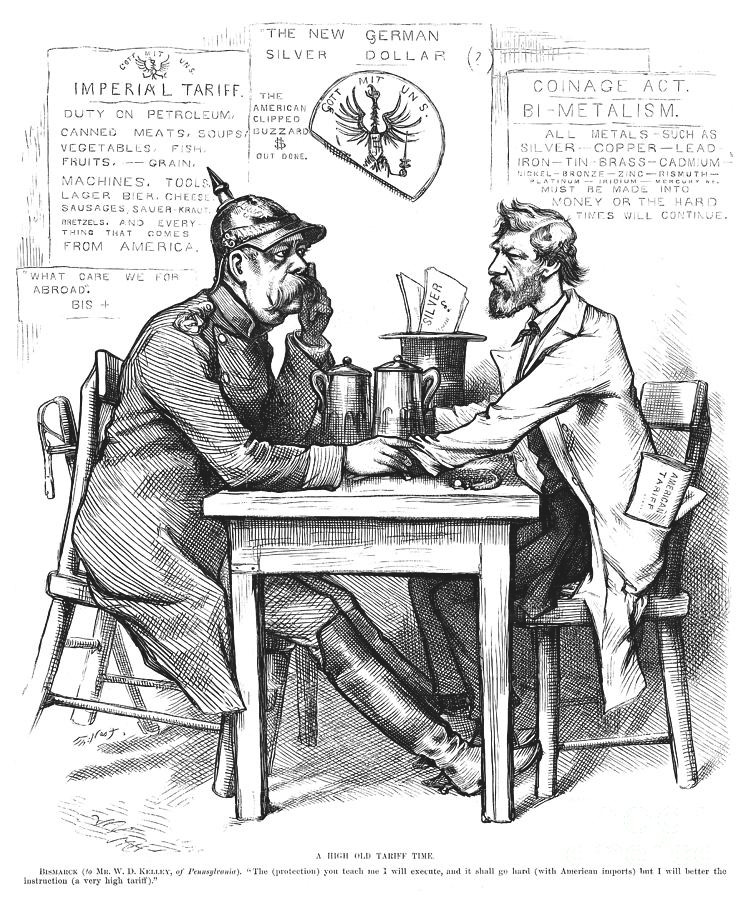

One of the foremost examples of the success of tariffs was Otto von Bismarck’s protectionist policies during the 1880s and beyond. As noted two weeks ago, bacon may have been the overt catalyst for Bismarckian tariffs, but the actual lead up to its implementation paints a picture like that facing the United States coming off of its COVID-era spending spree.

Them Good Ol’ Boys Were Drinking Iron and Rye

In the mid 1870s, Germany began to see a weakening economy after years of tremendous growth. Politicians and the public quickly blamed globalization — particularly its effect on the fall in grain prices thanks to cheap American grain flooding the market. The politically powerful Junker class, landowners in the eastern part of the country, pressured Bismarck to employ tariffs. Bismarck complied, and even went a step further by also protecting Germany’s fledging industrialization sector. The result is what is known as the “Iron and Rye” tariff.

But this explanation, the standard accepted by most historians, has recently been challenged. Asaf Zussman’s detailed macroeconomic investigation, published in a Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research discussion paper, demonstrated that real grain prices in Germany, particularly for rye—the dominant crop—did not substantially decline during the critical years leading up to 1879.

Instead, Zussman offers a different reason for Germany’s economic woes: the Franco-Prussian War. Following Germany’s defeat of its Gaulian enemies, a five-billion-franc war indemnity was imposed on France between 1871 and 1873. This vast sum—amounting to more than 8% of Germany’s annual national product during those years—acted as a massive capital inflow, setting off a monetary and fiscal expansion unprecedented in 19th-century German economic history.

Flush with French gold, the German government dramatically increased spending, especially on military expansion and infrastructure. Prices surged, growth soared, and Germany officially transitioned to the gold standard. During this period, the German economy displayed all the hallmarks of a capital inflow boom: rapid output growth, rising inflation, appreciation of the real exchange rate, and a buoyant stock market. To dig further into the data, the growth in GDP jumped from two percentage points to around six per year. Consumer price inflation “went up from an average of one and a half percent per year in the 1860-70 period to almost seven percents [sic] during the inflow episode.”

But when the French indemnity payments stopped in late 1873, the boom collapsed into bust. From 1875 to 1878, Germany experienced near-zero growth, sharp deflation, and a real exchange rate overvaluation that left its tradable goods sectors reeling. Iron and steel, having expanded dramatically during the boom, suffered most from excess capacity and collapsing prices. Raw iron prices, for instance, fell nearly 40% from their 1873 peak to 1876, and production contracted sharply. Efforts by industrialists to secure stimulus through state spending failed, and attention quickly turned to protective tariffs.

As Germany’s economic pain deepened, a broad coalition of producers of tradable goods began demanding protection, including the Junkers. Bismarck seems to have required little persuasion:

“I leave undecided the question whether complete mutual freedom of international commerce, such as is contemplated by the theory of Free Trade, would not serve the interests of Germany. But as long as most of the countries with which our trade is carried on surround themselves with customs barriers, which there is still a growing tendency to multiply, it does not seem to me justifiable, or to the economic interest of the nation, that we should allow ourselves to be restricted in the satisfaction of our financial wants by the apprehension that German products will thereby be slightly preferred to foreign ones.”1

Thus, in 1879, Germany enacted a wide-reaching tariff on both agricultural and industrial goods. The rates were generally moderate, and did carve out exceptions for specific goods that would help German industry, such as raw cotton and coal.

One point of contention is that Zussman concludes that the tariffs were not necessarily a backlash against globalization like often portrayed by historians but rather a reaction to the end of the French indemnity payments. But, as seen in the piece on the pork tariff, primary sources clearly show that the public believed that the cause of their economic woes was due to cheap goods flooding the market from places like the United States – suggesting that there was undoubtedly a backlash against globalization, even if it was unwarranted.

Just like today, there was a large cohort of free trade supporters who vocally opposed the tariffs, and, as noted in Erich Eyck’s Bismarck and the German Empire, the debates forced large schisms in a number of political parties. But, to keep this article as short and sweet as possible, Eyck concludes:

“The apprehension voiced by free traders at the time was not justified by the event. Nobody doubts the enormous economic progress by Germany after 1879. How far this progress was due to protection is another matter.”2

Boom and Bust

It is hard not to see the similarities between pre-tariff Germany and the United States today. The coronavirus pandemic acted as its own “indemnity,” flooding the market with stimulus money that often mirrored the “boom” economy in early 1870s Germany.

Like in Germany, the U.S. stock market reached record highs during and in the aftermath of COVID-19. Like Germany, the United States was also plagued with inflation, peaking at around eight percent in 2022. Though U.S. GDP growth had some setbacks following the early days of COVID, U.S. real GDP has grown 14.6% from 2019 to 2025, beating the pre-pandemic trend by 4.0 percentage points as of 2025.

But almost all COVID relief policies have come to an end (though there are a few that are still active until September 2026, like relief funds for state and local governments). Fortunately, the conclusion of most programs happened in a staggered timeline, unlike the immediate cessation of French funds in the German economy. But Americans are certainly hurting; in fact, a post-mortem of the 2024 election lays the blame of Harris’s loss on the fact that two thirds of all voters deemed the economy “not good/poor.”3

A Most Inconvenient Paradox

Many of Trump’s surrogates – and Trump himself – have discussed how the economy was injured by fiscal policy during the COVID years, using terms like “hangover” to describe the current languid financial landscape.

Like Bismarck, Trump has turned towards tariffs as a potential remedy. But President Trump faces another issue: the tariff-growth paradox. Despite all the talk of how the president is inspired by the McKinley era protectionist policies, few outlets have covered how tariffs were almost universally successful before World War II, and how they have been unsuccessful afterwards.

Different papers cite different reasons for this strange anomaly. For example, a paper by Sebastian Geschonke theorizes that pre-World War II tariffs were simply correlated with growth and the root was price changes.

But this author found a paper by economists Michael A. Clemens & Jeffrey G. Williamson to be the most persuasive; their core thesis is that Wilhelmine Germany and other nations in the 20th century who raised tariffs were able to export products to countries with lower tariffs, which is what spurred economic growth. As summarized by the blog Pseudoerasmus:

“This is how I personally interpret it: Great Britain and others acted as free-trade sinks (my phrase, not C&W’s) for exporting countries such as the United States (and Wilhelmine Germany) which protected their steel and other industries. (Echoes of East Asia which benefited from US policy during the Cold War? It’s nice if there are countries willing to indulge your export-led development strategy without reciprocal openness.)”

In other words, the global environment – and the tariff relationship between two countries – seems to be the deciding factor as to whether tariffs will be successful or not, not the actual theoretical policies themselves.

Looking at these tea leaves, President Trump might be onto something vis-a-vis his desire to reframe tariff relationships, despite the harsh critics of his protectionist policies. Let us hope, for the good of the United States, that he will be able to repeat Bismarck’s run rather than that of the oft-cited Smoot-Hawley Act.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2220734

https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.239661/page/257/mode/1up?view=theater&q=apprehension

https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2024/11/08/donald-trump-us-election-kamala-harris-economy/