Societal trends and cultural, rather than political, events are usually the beat of A.H. Childs, but certain trends and events are of such significance that they transcend normal boundaries and cross over into the political. One such transcendent event occurred this past week – the publication of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue.

Since its inception, the Swimsuit issue has always sparked controversy. In more innocent times, the issue, because of its “provocative” subject matter, would precipitate the cancellation of subscriptions, usually accompanied by a flurry of letters from irate parents accusing the magazine of corrupting their children. It became an annual tradition for the magazine to publish gleefully the best of those letters in subsequent issues.

More recently, however, the Swimsuit issue has become controversial for other reasons. Over the past few years, the magazine has included so-called plus-size models, and recently has begun to feature transgender individuals as well. This move has occasioned blowback by more traditional readers. Last year, psychologist Jordan Peterson ignited a firestorm when he tweeted about the inclusion of plus-size model Yumi Nu on the issue’s cover: “Sorry. Not beautiful. And no amount of authoritarian tolerance is going to change that.” This year, the magazine appeared to up the ante, featuring an 81 year-old Martha Stewart, a transgender singer, an actress with well-publicized body dysmorphia, and one traditional model on its four covers. The Babylon Bee had a lighter, yet more devastating take than Peterson, with the headline:

Dad Punishes Misbehaving Son By Giving Him Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue

The current issue has been criticized as an unnecessary foray into politics, following a path that Sports Illustrated appears to have chosen some time ago. Others merely see it, regardless of the politics, as but another example of the decline of a once prestigious magazine.

It is hard to argue with the latter perception. Ask virtually any long-time subscriber to Sports Illustrated or, more likely, one who gave up his subscription long ago, and he will lament that the magazine, which once was must-reading, is not what it was. There is also substantial merit to the argument that the Swimsuit issue has declined in a trajectory that mirrors that of the magazine as a whole. But the argument that the Swimsuit issue unnecessarily introduces politics is on less firm ground. There is a surprising amount of research into the history of pin-up pictures, a genre of which the Swimsuit issue is just another example, and many researchers argue that politics has always played a part in that genre from its inception. Pin-ups merely reflect the politics of the age, and Sports Illustrated of today is no different from publications of the past.

Sports Illustrated In The Past

It is difficult to remember the place that Sports Illustrated, along with its fellow publications, Time and Life, once held in the United States publishing world. While it never reached the circulation levels of the latter two publications, Sports Illustrated, in many respects, bettered them in terms of prestige. To a certain segment of America, Sports Illustrated was the pre-eminent sports publication, the Bible of sports as it were. Its stature was such that it could recruit the finest writers in the country to grace its pages. William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Robert Frost, and John Updike are all among the authors who wrote articles for the magazine.

To be sure, the magazine catered to a select, if not elite readership, one coveted by advertisers. Its coverage included not just the major sports, but also those that had little appeal to the average fan, including Davis Cup tennis, crew, and even bridge, which were of greater interest to its upper crust subscribers. Indeed, in one issue, the magazine covered not just the Harvard-Yale football game, a game that had long since become irrelevant to all except to select East Coast readers, but it wrote an article about the annual clash between the schools’ intramural teams (each Harvard House team would play a Yale College team).

Peruse an old SI issue online, and one will see a quality of writing that is virtually non-existent in sports writing today. Set forth below is the opening paragraph about an upcoming bout between Buster Mathis, heavyweight champion of the 1964 Olympics, and Joe Frazier, who became the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world when he defeated Muhammad Ali. The fight was the first major boxing match to take place in the new Madison Square Garden at Penn Station, and the author, Mark Kram, found the venue as significant as the fight itself, writing about the old Garden on 50th Street and Eighth Avenue:

Already, on this sad-sick street of smeared windows filled with old school rings and dusty old Army overcoats, of saloons with long, stained bars and strange lighting, the feel is gone. Just the building, a big-hipped slattern of design, remains. The old Garden echoes only the sounds of a night watchman’s clock and chain and the snores of bums sleeping in the cold dark of the outer lobby. The wind whips at the empty marquee, the images form in the mind, of dance kings and sluggers, of a thousand tableaus that no longer hang there anymore.

In the ADHD-style of sports writing that dominates the media today, one wonders not just whether a writer would write such a paragraph, but whether he could.

While the magazine no longer appeals to a certain elite on the basis of its writing, it does another in one respect. There can be little dispute that SI has injected politics -- uniformly progressive -- into its pages. The magazine has long supported controversial athletes such as Colin Kaepernick and Megan Rapinoe, but its coverage has gone beyond political issues that affect only sports to issues that have little to do with it.

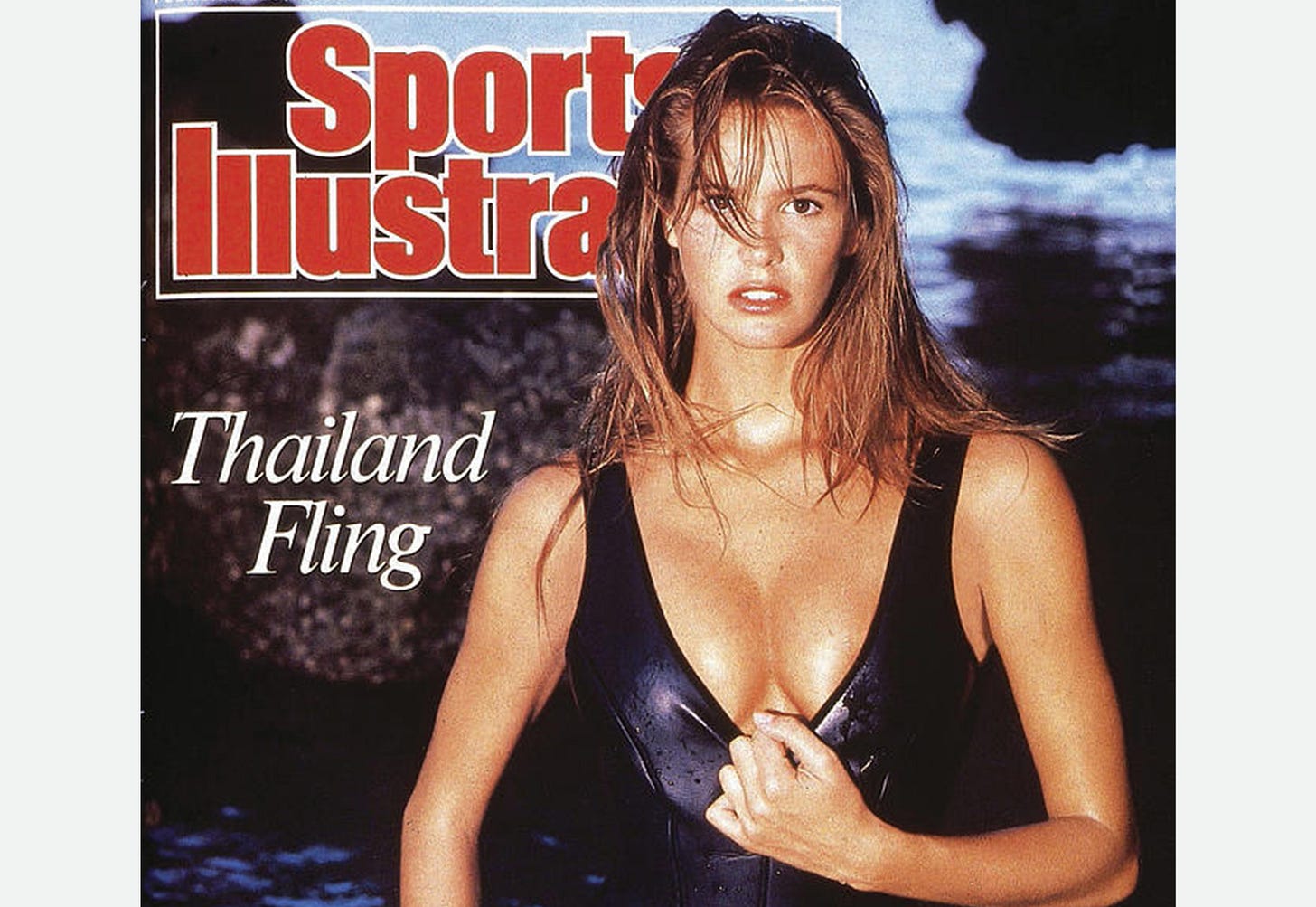

The Swimsuit issue has more or less followed the arc of the magazine. It famously began as an afterthought in 1964, when the magazine needed filler for a winter issue. It went from a cult favorite to a national powerhouse, creating stars out of Christie Brinkley, Elle Macpherson, and Kathy Ireland among others. Beginning in 1997, it became a standalone issue, and, in the following years, the announcement of the cover models was made on national television.

The emphasis of the issue began to change in 2015 with the introduction of SI’s first plus-size model, Ashley Graham. Graham went on to grace the cover the following year. The direction of SI’s photoshoot can be gleaned from the list of this year’s so-called eight “rookies,” which include 3 plus-size or “curve” models. The magazine does not include in its Rookie Class transgender singer Kim Petras or Martha Stewart, which serves even further to broaden the “diversity” of “body types” featured in the magazine. The biographies of virtually all of these models emphasize their advocacy for various causes, be it LBGTQ rights, body positivity, women entrepreneurship, or animal preservation. It could be argued that Sports Illustrated has created the conceptual model where, just as in conceptual art, the story behind the model, and the reason for her inclusion, is of equal or greater importance than her actual physical beauty.

While the overt, if not heavy-handed introduction of politics into the Swimsuit issue has angered many, it is not unprecedented. Indeed, it has always been a part of the pin-up genre.

Politics and the Pin-Up

Although there is some disagreement as to when the pin-up was created, many date the modern pin-up from around World War II. Prior to that date, there had been many antecedents. The Gibson Girl, discussed by this site in "That Girl" Was Originally A Gibson Girl: Why The Viral TikTok Trend Actually Began 100 Years Ago, arguably was the original progenitor. Thereafter, pictures of beautiful women began to appear routinely on calendars, leading to the term “calendar girl.” The most famous was the nude “September Morn,” printed on hundreds of thousands calendars and other products, notwithstanding the opposition of the Anthony Comstock and the New York Society for the Prevention of Vice, the subject of our post, How Twitter Became The Modern "Vice Squad." They were also used in advertisements. One famous painting,” Psyche at Nature’s Mirror,’ became the worldwide symbol for White Rock beverages. However, these pictures tended to be illustrations rather than photographs. Such illustrations became the staple of men’s magazines, most notably Esquire, which featured the “Vargas Girl” and the “Petty Girl.” One Petty Girl, clad in a rabbit suit, is said to have inspired Hugh Hefner to create the Playboy Bunny.

Esquire is best known for featuring illustrations of pretty women, but, as photography began to replace the illustrator, some scholars credit Life with introducing the modern pin-up. The magazine did this covertly, using seemingly anodyne articles as an excuse to introduce images of attractive young women. For example, Life began doing a series of articles about life on college campuses. These articles tended to include pictures of attractive coeds, including a controversial picture of a Drake University student taking a shower that almost resulted in her expulsion. These articles became less subtle as time passed. Articles about exercise had pictures of fit young women in exercise gear, frequently doing exercises that showed off their legs. Articles about knitting were a pretext to include pictures of busty women in tight, knitted sweaters. Life would chronicle the decline of burlesque by including photos of performers scantily clad in lingerie.

The pin-up came into the open with the publication by Life of an article, in July of 1941, about Dorothy Lamour as “the No. 1 Pin-Up Girl of the U.S. Army.” That same year, the United States entered World War II, an event that, to some scholars, had a profound effect on the proliferation and substance of pin-ups.

One of the best-known studies in this regard is the essay, "I Want a Girl, Just Like the Girl that Married Harry James": American Women and the Problem of Political Obligation in World War II, written by Robert Westbrook of the University of Rochester.1 Westbrook posited that the United States government utilized and influenced the pin-up genre expressly to incentivize the soldiers and sailors fighting the war. He argued that, particularly in liberal democracies, soldiers were more highly motivated by private interests than public ones. One of the principal interests for which American soldiers fought in the war was American womanhood. Westbrook saw evidence of this in the fact that the most popular pin-ups were not titillating or erotic, but ones that reminded them of home. As Alan Ladd observed, while serving on the Hollywood Victory Committee, servicemen were not interested in “flash,” but in “girls they can prize.” He noted that they preferred movies “whose components – street scenes, normal people on the streets, women who look like mothers, wives, sweethearts—bring them near home.” Westbrook also noted how private symbols of women that soldiers placed on planes and tanks were of equal or greater prominence than the national symbols.

This fact explains the popularity of Betty Grable, the most sought-after pin-up of the war. Grable embodied an American ideal, “sincere, honest, with both feet on the ground.” Particularly when compared to a sexier pin-up, such as Rita Hayworth, Grable was no siren. As Time magazine put it, “she can lay no claims to sultry beauty or mysterious glamor. Her peach-cheeked, pearl blonde good looks add up to mere candy-box-prettiness.” That Grable represented an idealized America was reflected by the fact that, as Time also reported, soldiers preferred Grable to other pin-ups “in direct ratio to their remoteness from civilization.”

According to Westbrook, the American government was not only aware of the power of propaganda utilizing American women, but encouraged it, using the pin-up as a motivational tool for the country’s servicemen. Another scholar of pin-up art, Michael West of the University of Iowa, while discounting Westbrook’s overarching thesis, acknowledges that the power of the pin-up was not its sexuality, but its reflection of home life.2 He demonstrates this by reference to Life magazine and regional papers of the period, documenting that, as World War II progressed, the glamorous Hollywood pin-up was replaced by pictures of everyday women -- wives and mothers – primarily at the request of overseas servicemen. These publications began with debutantes and college students, but soon replaced them with winners of local beauty contests, run by corporations or other private entities.

To Westbrook, the phenomenon of the pin-up was inextricably woven into national politics. Other scholars agree, but from a completely different perspective. While Westbrook saw the pin-up phenomenon through the lens of traditional masculinity, Maria Elena Buszek, Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Colorado Denver, saw pin-up art as an expression of feminism. In her book, Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture, Buszek argued that the pin-up phenomenon occurred during a period of consolidation, if not regression, in the woman’s movement. She placed this period from 1920, after women achieved suffrage, to 1960, when the sexual revolution helped fuel the revival of that movement.

Ashe argues that the pin-up was the essential precursor to the women’s movement in the sixties, providing a model, necessarily subversive in a period of reaction, that “circumvented antifeminist postwar ideals in ways that would logically evolve into the full-blown second wave of the women’s movement in the 1960s.” This subversive model was represented by the Varga girl, about which Buszek wrote:

The Varga Girl presented the American public with a heretofore unheard-of combination of conventional beauty, blatant sexuality, professional independence, and wholesome patriotism that resembled the similar, contradictory cocktail of attributes cultivated by young women of the period. With the entire country focused on (even pandering to) youth as their strength and stamina were needed to lead the country into war, young Americans’ fascination with the pin-up became the country’s, and the Varga Girl a subversive icon for the sweeping changes in gender roles and sexual mores that developed during World War II.

Buszek’s thesis is visible in the latest iterations of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit edition. The 81 year-old Martha Stewart, the plus-size Ashley Graham, and the transgender Kim Petras are as much transgressive symbols as were the Vargas Girls 90 years ago. The pictures are far more political than they are erotic. As a consequence, SI is merely following a precedent set long ago.

Does Politics Sell?

As this article hopefully demonstrates, both the critics and supporters of Sports Illustrated may both be right. The critics are right that the magazine is not what it was, and that it has intermingled politics with entertainment. Supporters argue, with merit, that politics is inevitably intermingled with art, and that the symbolic value of the current Swimsuit issue is both powerful and beneficial. Whether one agrees with Westbrook, or one agrees with Buszek, the Swimsuit issue is, by its nature, political.

This disjunction, however, presents Sports Illustrated with a dilemma: Does the magazine emphasize its political message at the risk of alienating long-time readers, à la Bud Light and Target, or does it revert to providing traditional, or even reactionary entertainment? Only time will tell. But the difference for Sports Illustrated is that the majority of those long-time readers are probably already gone.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2713166

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#inbox/FMfcgzGsnBbwHJMKmTkFccTZKXnsHLjx?projector=1&messagePartId=0.1

Great read, and your conclusion is very satisfying. How many of those classic SI readers even follow the publication anymore?

It feels right, and you also give enough evidence that makes it also sound right, too. Thanks so much for this one John!